Why cleaning up used vehicle markets is essential as we shift to electric vehicles

To encourage higher quality vehicle imports and avoid locking in carbon emissions with dirty, combustion vehicle technology, emerging economies have started enacting used vehicle import restrictions.

On the streets of Nairobi or New York City or Bogotá, most cars you will see were not purchased new from a dealer. Cars pass through various owners over their lifetime, crossing borders, undergoing maintenance, and eventually being picked apart for parts or recycling.

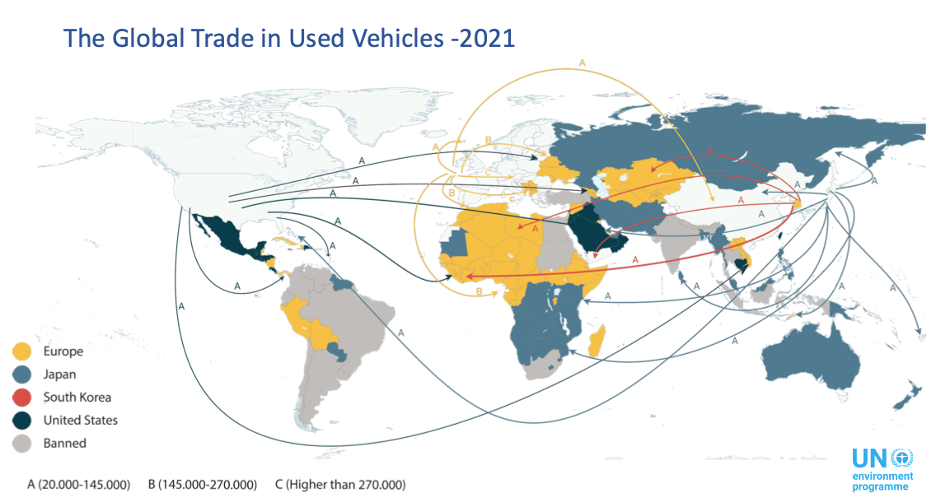

For this reason, transportation decarbonization is not simply a story of new sales in major markets. In low- and middle-income countries across Africa, Asia, and Latin America, used vehicles are often imported after cycling through several owners in the U.S., Europe, Japan, or South Korea. In Nairobi, Kenya, for example, a local produce vendor like John Mwangi relies on his imported Toyota to run his business, yet the 22-year-old vehicle arrived in Kenya as part of the global flow of cars that are deemed too polluting or unsafe for the roads in higher income countries.

Between 2015 and 2018, 14 million used light-duty vehicles were exported worldwide, according to research by the United Nations Environment Programme (UNEP). Some 80% went to low- and middle-income countries, with more than half going to Africa. While used imported combustion vehicles can be a relatively low-cost mobility option, they can bring a hefty price tag in terms of air pollution, greenhouse gas emissions, and harm to human health. These vehicles are often less safe and much dirtier than the global average, either because they were certified to older emissions or safety standards, or in some cases the vehicles have been stripped of equipment that control emissions, like filters.

To meet climate goals, we need to move the global market of vehicle production toward zero-emission models. Our work with Drive Electric partners is already transforming vehicle markets, and used electric vehicles (EVs) are now popping up around the world — a rapidly growing market that is providing an opportunity for low- and middle-income countries to access affordable electric vehicles.

Yet the global nature of vehicle markets and supply chains means we need a coordinated, global strategy to be successful. Estimates from UNEP project that the worldwide fleet of passenger vehicles is set to at least double by 2050, and over 90% of this growth will take place in emerging economies. This growth consists of both domestic and imported new vehicles as well as imported used vehicles.

To encourage higher quality vehicle imports and avoid locking in carbon emissions with dirty, combustion vehicle technology, emerging economies have started enacting used vehicle import restrictions. With guidance and support from UNEP, governments deploy trade policy to improve the efficiency and safety of used vehicles crossing their borders, while also preferencing clean, zero-emission imports.

As UNEP explains in their landmark Used Vehicles And The Environment publication, the most effective trade policy regimes combine various measures that touch upon the entire vehicle lifecycle, including on-road inspections, enforcement and maintenance, scrappage, and recycling. Since the 2020 report release, more than 30 countries have begun adopting new standards that limit polluting vehicle imports in favor of cleaner cars.

UNEP works directly with national governments as well as regional governmental bodies to help design policy combinations that align with the underlying market conditions and policy goals. These trade policy options lead to a safer and cleaner fleet, and at reasonable costs. This can look like mandatory vehicle labeling to include emissions or fuel economy information, or providing minimum standards for safety or emissions, as well as selective or complete bans. For example, Egypt had initially banned all used vehicle imports, but then changed the law to allow the import of used EVs. In a different model, Kenya has halved the excise tax to attract more used and new EVs, and the import of used EVs has grown much faster relative to used combustion vehicles.

The small island state of Mauritius has been at the forefront in Africa on introducing cleaner vehicles policies. They introduced a “feebate” where taxes were increased on vehicles with large combustion engines and reduced on small engines and EVs. The import of used EVs has multiplied. Meanwhile, Sri Lanka has high taxes for petrol vehicles – especially diesel models – and low taxes for hybrid and electric vehicles. As a result, their relative share of used hybrid and electric vehicles is the highest of any country in the world.

When a country changes what kinds of vehicles are available in the market, there is a direct climate emissions impact. For example, applying an age limit ban based on a vehicle’s model year means that used vehicles older than the set age would not be imported, and thus the fleet becomes newer and more efficient. UNEP estimates that going from an average vehicle that is 20 years old to 5 years old can save up to 10% of fuel and CO2 emissions. This can also increase the proportion of used electric vehicles in the imported vehicle fleet as leading markets like Europe, California, and South Korea are committed to 100% zero-emission passenger vehicles for all new sales by 2035.

The true strength of this approach is that these policies help tip market access to favor cleaner options that lower the total cost of ownership of vehicles. And this approach is not limited to private cars: import restrictions can ensure that the dirtiest trucks and buses are scrapped rather than given a second lift to pollute the world’s fastest-growing cities in emerging economies. With these modest tweaks to trade policy, we can dramatically increase the quality of imported products with a low regulatory burden in terms of time and costs.